|

|

Raynor Whitely Speaks about Freight Handling |

|

|

Hugo Carlson Talks about Freight Going through Athabasca |

The Athabaska Landing is the gate of the great North. It is from here that all the stores go out that supply the Hudson's Bay Company's forts from Hudson's Hope to the mouth of the Mackenzie. A steamer built on the spot plies up the river to the mouth of the [Lesser] Slave River, and down to where the rapids make the Athabaska no longer navigable, where the stores are transshipped to York boats. Beyond the warehouses, offices, and Mr. Wood's residence there are no buildings, although most of the year there is a large Indian encampment near by. It is, too, the last outpost of the Government . . . (Pollen quoted in Athabasca Historical Society 1986, 35)

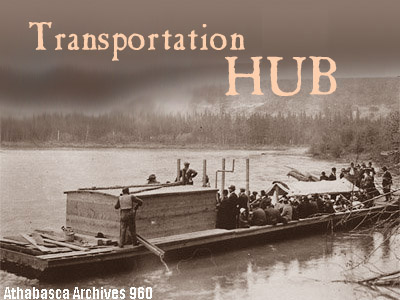

Athabasca Landing became increasingly important to the Hudson's Bay Company's trading network in the north-west, primarily as a transportation centre, rather than a trading outlet. The Company employed Indian and Métis labour to build and guide the scows used to move freight up and down the Athabasca River. Known as the "Athabasca Brigade," these several hundred boatmen loaded and navigated the bulky scows, steering them through the rocks, ledges, and rapids of the Athabasca River:

These were a boat of about 35 or 40 feet in length and 10 or 12 feet wide which would hold about 10 or 12 tons. Each was equipped with a long sweep and four oars, and a crew of five men, who used the oars when needed to get the boat out into the river or back to the shore, but were mostly hired to handle freight that had to be unloaded to lighten the scow when running some of the rapids later on. (Captain Julian Mills quoted in Parker 1980, 15)

Tracking, as the hauling of cargo-laden scows was called, was an arduous task where a team of eight to ten men pulled boats upstream.

Nothing indeed can be imagined more arduous than this tracking up a swift river against constant head-winds in bad weather. Much of it is in the water, wading up "snies," or tortorous shallow channels, plunging into numberless creeks, clambering up slimy banks, creeping under or passing the line over fallen trees, wading out in the stream to round long spits of sand or boulders, floundering in gumbo slides, tripping, crawling, plunging, and, finally, tottering to the camping-place sweating like horses, and mud to the eyes . . . (Zinovich 1992, 98-99)

Things changed when steamboats were constructed at the Landing to ply the central section of the Athabasca River from Mirror Landing to Pelican Portage. The S.S. Athabasca, launched in 1888, was "162 feet long and nearly twenty-eight feet wide, with a draft of four feet, and her Captain was John Segers."

[N]ot a fast boat — the round trip from the Landing to Grand Rapids and back sometimes took about a week — but she was capable of carrying more cargo and of making more trips than the HBC actually required to supply its northern posts. (Athabasca Historical Society 1986, 38)

If steamboats helped establish Athabasca Landing as the HBC's "headquarters of northern transportation" and "gateway to the north," weak links in the route still remained. One was the series of rapids from the Grand Rapids north, which the Athabasca Brigade had never completely tamed. Time was lost transferring cargo from the boats to a flatcar on the narrow, wooden-gauge railroad that had been constructed on the island in the centre of Grand Rapids, and then reloading it into the scows and York boats on the other side. Clearly, less cargo was lost when the boats went over the rapids empty. But it wasn't a perfect solution; lives and freight were still lost here occasionally and in bad weather some of the other rapids downstream also drowned their share of men.

Soon, however, the HBC monopoly was under pressure from freetraders such as Hislop and Nagle (1891), rival fur trading companies such as Revillion Frères (1904), and a rival transportation firm, the Northern Transportation Company (NTC), which arrived at the Landing to compete with the Hudson's Bay Company in 1903. Founded by Jim Cornwall, Fletcher Bredin, and J.H. Woods, the Northern Transportation Company expanded rapidly with its stern-wheeler, The Midnight Sun, taking over nearly all the non-HBC freight and passenger traffic that the S.S. Athabasca had once carried to Lesser Slave Lake 220 miles west, and to Grand Rapids 156 miles north. Soon the NTC had "enough capital to construct The Northern Light — a shallow-draught side-wheeler designed to operate on the shallower Little Slave River and on Lesser Slave Lake. The HBC, in contrast, had to make do with scows. . . ." (Athabasca Historical Society 1986, 82)

Here is a description of a typical scow:

Each boat's crew consisted of seven Indians, one of whom acted as guide or steersman, and handled the ponderous "sweep". One was bowsman, and the five others were oarsmen whose duty it was to pack the goods across the portages. Each scow carried about 180 pieces, each piece representing 100 pounds on average. All the goods for the north are put up in hundred pound lots, or as near that quantity as possible, so that they may be the more easily packed on the portages.

The first thing in the boat was a tier or two of bags of flour, extending from bow to stern. Then came sides of bacon, sacks of rice, caddies of tobacco, bags of shot and bags of balls, boxes of rifles, boxes of raisins, crates of hardware, pails of candles, stoves, medicine chests, kegs of powder, bales of twine for net making, blankets, ready-made clothing, dress goods, tea, etc., all piled in without much order; the only care exercised in their placing being to see that the boat rides level. (Mathers quoted in Athabasca Historical Society 1986, 82)

![]()

Home | Hudson's Bay Company Post | The Landing Trail | Society, Gender, and Race | Transportation Hub | Boatbuilding | To the Klondike | The Commercial Boom | Amber Valley | The Athabasca Bore | Agriculture and Settlement | Then and Now