Here we have a large establishment of the Hudson’s Bay Company, an Anglican and a Roman Mission, a little public school, a barracks of the Northwest Mounted Police, a post office, a dozen stores, a reading-room, two hotels, and a blacksmith shop, and for population a few whites leavening a host of Cree-Scots half-breeds.

Athabasca Landing is part of the British Empire. But English is at a discount here; Cree and French and a mixture of these are spoken on all sides. . . .

(Observations by Agnes Deans Cameron about Athabasca in 1908, quoted in Athabasca Historical Society 1986, 152)

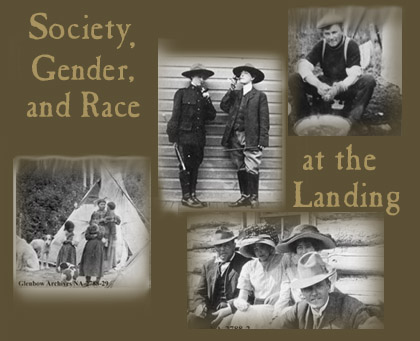

How do we recover a history of First Nations and Métis peoples at Athabasca Landing? And how might we recover the history of women – First Nation, Métis, pioneer, or settler - at the Landing? While our understanding of white men and their commercial activities is well-documented, the activities and views of First Nations peoples, the Métis, and women are often available only obliquely, through the eyes of those white males who took the photographs or recorded the history of the Landing.

Athabasca Landing is a place that few outsiders knew about less than two hundred years ago, even though it had for thousands of years been known to the First Nations peoples who lived 40 miles north in the Calling Lake area. As historical geographer Cole Harris writes, most Canadians are "immigrants --– we are here, because we have imposed ourselves." Ours is a history of colonialism – and particularly a history of white males – who brought with them western European ideas about capitalist enterprise and industry, and the control of First Nations and later Métis populations. And, who espoused views of progress, reason, and religion that they imposed upon the west, and the peoples who had lived here for thousands of years. (Cole Harris 1997, xii)

This fact is immediately clear when examining photographs of the Landing and reading their subtitles. White males are recognized by name and title, First Nation and Métis peoples remain anonymous. Certain white women are named, but usually only because of their association with important male figures – such as a Hudson’s Bay Company manager’s wife, or female members of the families of religious ministers or businessmen. Cree and Métis trackers and boatbuilders, First Nation and Métis women who cooked or laboured around the landing, or the white and Métis women who accompanied their “men” to settle and open the farmland of the West - remain for the most part anonymous. Their histories have yet to be written.

As the Athabasca Historical Society notes in Athabasca Landing: An Illustrated History, if you look carefully, glimpses of “the frontier community can be found” with its “ethnic mix of Cree, Métis, and British Canadians.” He describes a well-defined system of social stratification.

At the bottom of the social ladder were the Indian families. One step higher were the ordinary Métis boatmen and labourers, and their women and children. A cut above them were the smaller group of river pilots, the men such as Captain Shot who led the scow brigades and who supervised the annual ritual of boat construction at the Landing. They were the only non-whites who had won and retained the grudging respect of white society. . . .Moreover, in addition to this racial-cum-linguistic barrier, the Landing’s social structure exhibited a strong degree of class stratification among those of European extraction. At the bottom . . . were the wage-labourers and other paid employees who could be dismissed at will when their services were not required: the loggers, freighters, sawmill hands, carpenters, painters, shop-assistants, transportation clerks, waitresses and cleaning women. Their status was higher than that of the Métis boatman, but lower, perhaps, than Captain Shot's. Above them in the social pyramid came the skilled craftsmen, such as blacksmiths and harnessmakers; the independent fur-traders. . . .

Entry into the Landing’s social élite required wealth, education, or a professional job. This respectable stratum included Athabasca’s most successful businessmen, bank and trading company managers, government officers, police inspectors, doctors and clergymen, and, of course, their wives and offspring. It supplied the Landing with its mayor . . . councillors, its Board of Trade members, School Board members, churchwardens and Sunday–school teachers, as well as the presidents of such local societies as the Canadian Club, the Overseas Club and the Freemasons. . . . The wives and daughters of these influential men were known collectively as “the ladies of the landing”. . . (Athabasca Historical Society 1986, 155-156)

These patterns of social stratification set a special challenge for visitors to the Historical Athabasca Landing 1880-1914 web site. We urge you to consider the labour done by the anonymous workers and trackers, to lift from the background the image of the First Nations and Métis peoples, to think critically about the colonial social relations of men and women, and whites and non-whites, as depicted in the photographs and diary descriptions of the Landing.

For examples of new scholarship that takes up these ways of seeing consider:

K. Coates and Robin Fisher, Eds. Out of the Background: Readings on Canadian Native History. 2nd Edition. Toronto: Copp Clark Limited, 1996.

Cole Harris, The Resettlement of British Columbia: Essays on Colonialism and Geographical Change. Vancouver: UBC Press, 1997.

J. Mouat and C. Cavanaugh, Eds. Making Western Canada: Essays on European Civilization and Settlement. Toronto: Garamond Press, 1996.

Home | Hudson's Bay Company Post | The Landing Trail | Society, Gender, and Race | Transportation Hub | Boatbuilding | To the Klondike | The Commercial Boom | Amber Valley | The Athabasca Bore | Agriculture and Settlement | Then and Now