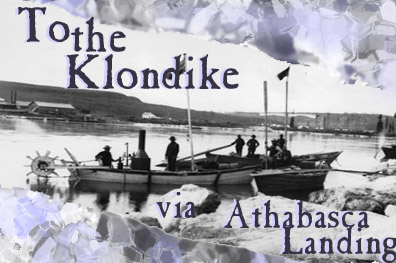

Klondikers preparing to leave for the Yukon gold fields.

Provincial Archives of Alberta, B5200.

In Athabasca Landing: An Illustrated History, the Athabasca Historical Society asks "why did nearly 800 prospectors choose the Athabasca River as their road to riches in 1897-98?" They tell us how in the summer of 1897, John Segers, captain of the S.S. Athabasca, declined to renew his contract with the HBC and began making preparations to lead a ten-man party of prospectors to Dawson City in the Yukon. Segers’s decision, motivated by desire for adventure as much as the lure of gold, was the first of many changes that Athabasca Landing would witness during 1897 and 1898 as it became caught up in the fever and frenzy of the Klondike gold rush.

In fact residents at Athabasca Landing received word of the gold strike in Alaska a full two months before major American newspapers made “Klondyke” a household word. Segers and some 30 other groups of prospectors grabbed a head start on the main stampede from California and on the 700 - 800 or so that chose to pass through Athabasca Landing in the next twelve months via the "poor man's" or "overland route" to the Klondike.

The papers were full of the news and a lot of lies, which we were to find out later; but at that time it appeared that all we had to do was to go to Dawson City and pick up as much gold as we wanted. . . . The first thing to do was to determine which way to go, for there are three ways of getting into the Klondyke. We consulted our friend . . . and he told us he had heard very bad accounts of the Skagway Trail, so we went off to Edmonton and from what we heard there we decided to go in by the Mackenzie River route. We built a big fine boat, bought sufficient provisions to last a couple of years, put the lot in two wagons and started off for Athabasca Landing. The wagon road to the landing was good and we made the 100 miles in four days. After a couple of days to put things right and land the boat, we started out down the Athabasca River on the 2nd September, 1897. The weather was lovely, the mosquitoes all gone, the sun shining warm and bright. We were off on our 4,000 mile journey, carried along by a good four knot current. (Milvain quoted in Athabasca Historical Society 1986, 58-59)

The all Canadian water route to the Yukon was half the length of the American route, and 775 prospectors attempted the 2000 mile trek northward. Most Klondikers stayed at the Landing only long enough to get supplies and build a scow. A second wave of gold seekers reached Athabasca Landing in the winter of ’97 and ’98 transforming it from a “tiny settlement...with a transient population with 40 or 50 white people...(and) a couple of hundred Indians” into a cosmopolitan tent city of “at least a thousand strangers.” They were lucky that it was a mild winter for living under canvas. The following is a description of the Landing in April of 1898, as a third wave of Klondikers arrived:

Less than three months ago the “Klondiker” upon descending the winding slope leading to the river bottom which constitutes the location of the village, saw only the Hudson Bay fort warehouse and out-buildings, the Athabasca, saw mill and English church, the police barracks, two houses, a few shacks, and train dogs galore; high hills, snow two feet deep and all is told. Today the scene is changed. The scores of white tents that dot the hill side and the river bottom almost succeed in sustaining the snow impression of two months back . . . East and West Chicago are places or camping grounds east and west of the village proper and so-called because of the Chicago men there who outnumber their fellow campers four to one. (The Edmonton Bulletin quoted in Athabasca Historical Society 1986, 61)

Athabasca Historical Society estimates that "at its height the transient population probably reached 1,000. . . ." Some decided to go no further and settled at Athabasca Landing because "Good money could be made at the Landing during the spring by merchants, carpenters and experienced boatmen." For example, a commercial sawmill was opened by Alex Fraser, and a boatyard by J.H. Woods and S.B. Neill, and:

. . . several men who would become well-known local figures first came to the Landing in 1897-98: "Peace River Jim" Cornwall who worked as a river pilot; Joseph Daigneau who began his career in Athabasca as a carpenter; C.B. Major, a French-Canadian freighter who subsequently homesteaded north of Baptiste Lake; fur-trader Peachy Pruden who ran one of the general stores; and jack-of-all-trades William Rennison who was initially employed by Pruden in his store and a few years later became the Landing's first Postmaster. (Athabasca Historical Society 1986, 62)Of those Klondikers who forged ahead, at least 35 perished along the way (mainly from drowning or scurvy), perhaps 160 eventually reached Dawson (mainly in 1899), and all the rest turned back or were rescued by relief expeditions. One prospector, R.H. Milvain, recorded his yearlong trip. He started up the Athabasca River to Fort McMurray and Lake Athabasca, northwards from Fort Chipewyan along the Slave River to Fort Resolution on Great Slave Lake, westwards across the Lake to Fort Providence at the head of the great Mackenzie valley, and then down the Mackenzie River through Fort Simpson, Fort Norman, and Fort Good Hope to Arctic Red River and Fort McPherson at the southern end of the Mackenzie Delta. The most difficult part of the route was a fifty-mile toil up the Rat River to the heights between the Mackenzie Valley and the Porcupine River Basin, but once going through the Richardson Mountains, it was downstream again on the Bell and Porcupine rivers to Fort Yukon. "The last stage, 300 miles south-east to Dawson, was a steamboat ride or a wearisome but not dangerous pull against the current of the broad Yukon River to its confluence with the Klondike." (Athabasca Historical Society 1986, 59)

The Klondike rush put Athabasca Landing on the map, “From 1898 onwards Athabasca Landing was much more widely recognized as a gateway to the far North-West.” (Athabasca Historical Society 1986, 53-67)

![]()

Home | Hudson's Bay Company Post | The Landing Trail | Society, Gender, and Race | Transportation Hub | Boatbuilding | To the Klondike | The Commercial Boom | Amber Valley | The Athabasca Bore | Agriculture and Settlement | Then and Now